A Service Application – Bottle Blower

Usually my work involves designing and building new equipment, or occasionally completely rebuilding and upgrading old machines. Last week I got an emergency call from an existing customer that their production line was down and they couldn’t get help quickly enough from the vendor; could I please come down and see what I could do?

Typically I avoid this kind of situation. The designers and builders of a machine know their product much better than I do, and if it is beyond the ability of a plant’s maintenance department to solve the problem, it may be beyond mine too.

In this case, my customer is very valuable to me and I knew that they wouldn’t have called unless they really needed me, so I hopped on a plane and was there the next day.

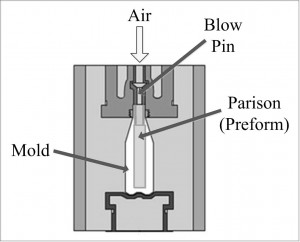

My knowledge of PET bottle blowing was largely theoretical. In my book there is a section on plastics manufacturing and processing, within which is a description of blow molding. Here is a picture of the process that gets the point across pretty well:

The picture of the machine at the top of this post shows the Parisons, or preforms, feeding into the machine.

After looking over the machine and talking with the maintenance manager I determined that the processor, a Siemens S7-400, was not running. They also did not have a copy of the program (more on that later…)

I was able to go online with the PLC and determine that the program was at least present, and that there was an I/O fault. Siemens software allows faults to be addressed by calling special routines or OBs (Organization Blocks) allowing the processor not to leave run mode. In this case the particular routine or OB that would have prevented this was not in the program. This was a conscious decision by the OEM, Sidel. Since the HMI ran on a different (BASIC) module, it could still be used to display messages to help determine the problem, but unfortunately it was not communicating either.

As I mentioned, my customer did not have a copy of the program. Some OEMs consider their software to be proprietary and don’t want anyone to see how they control the machine. Others lock down the software so that it can’t be changed, partially to ensure that their customer can’t mess it up. In this case both were true, but I was still able to go online and at least determine what the problem was. The down side is that without a commented program, it is nearly impossible to follow the logic. It wasn’t necessary to follow the logic in this instance, the problem was with the hardware.

Most of the major control components were in a big three door free-standing cabinet. There were two remote I/O nodes on Profibus inside of the machine, they were connected using a rotary union and actually rotated with the molds. A series of slip-rings and brushes passed the signals and power to the panels. Wherever things are moving, that is a good place to start your troubleshooting. In this case, the remote Profibus nodes showed a communication fault. There were three different connections to check, after a bit of investigation we determined which one had the problem. This was fixed pretty quickly and we moved on.

After getting the processor back into run mode we also found a problem with the safety circuit. I described how a dual channel safety circuit works in a previous post; they can be quite complex with a lot of connections. This was certainly true in this case. In the interest of testing whether the rest of the machine was operating correctly, we bypassed the circuit at the panel and started the machine. It was able to run and I headed back home shortly afterward.

During this time I had given Sidel a phone call to discuss the machine. They confirmed that they did not give a copy of the program to the customer, which as I mentioned is not that uncommon for OEMs. They said that usually they would have the customer send the diagnostic buffer using the software and that would allow the company to help determine the problem.

They also said that their technician could come down to the plant the following week and help with determining the safety circuit problem and whatever else may be needed. The customer said there had been issues previously with a technician showing up and not being able to fix the problem. I talked with the customer again this week and they said that it had happened again; the tech had left and the safety circuit was still bypassed. Of course they still had to pay for the service call.

A few things of note in this story:

1. It is often not necessary to understand the process well to fix the problem. In this case it was necessary to be able to go online with the program, but not necessary to be able to read it.

2. Communications and safety circuits are two of the most common controls problems with machinery. Typically things like sensor and actuator problems can be found easily if proper diagnostics are built into the HMI.

3. If there is a connection problem look at wiring around moving parts of the machinery first.

4. Give your technicians all of the information, tools and abilities to fix the problem before sending them to the customer site. I am also not a fan of protected programs or “know-how” protection, though I understand the vendor’s thinking. The frustration and problems this causes in my opinion outweighs the benefits. In this case the customer views the vendor as a last resort rather than a valued partner.

I think that there is probably a pretty good market out there for skilled service technicians. Probably the best way for someone to satisfy this market would be to concentrate on different niches; packaging, bottling, pharmaceutical/medical, process control and automotive assembly immediately come to mind. It is difficult to be an expert in everything, but there are already lots of skilled people out there in these fields.

As for myself, I have a lot of respect for those service people who can keep their customers happy. They generally see the customer at their worst, when production is down and the clock is ticking. They also have to be ready to travel at a moment’s notice and often don’t know what they are walking into, through no fault of their own.

I think I’ll stick to new, clean machines and a predictable schedule!

Super article …. really drives home the complexities involved these days with an awful lot of paranoia.

Good story, also totally in line with my experience in Marine Electrics/Electronics.

When it comes to OEM’s not suppling Dwgs/Manuals/Support the Yacht Industry is rife. The really big players like ABB ( I am not singling them out) are the worst (we cant supply you with drawings but we can supply a service technician at 1500 Euros per day)! and by the way its the same price for the travelling time from Italy to the Carribean.

I recently helped a 56 mtr yacht in Spain with a recalcitrant Shell Door, its hydraulics being controlled by a PLC. It was exactly an intermittent comms port and a displaced proximity sensor, virtually the same scenario as the bottle blowing plant!

You are right on! You must know the theory of operation to diagnose and correct problems that are one of kind. I get this calls all the time. The first I do is read the manual for information and look for what is abnormal. Great Job!