A few thoughts on panelbuilding…

It seems like there is a constant battle between mechanical designers, electrical designers, maintenance technicians and engineers over just what a properly fabricated control panel should look like. If it were up to mechanical, the panel would be the size of a breadbox and well hidden so that it wouldn’t destroy the clean lines of the machine. If it were up to maintenance you would be able to walk inside, turn on the light, sit down and fire up the laptop while sipping a beverage from the backplane-mounted vending machine. Engineers and electrical designers fall somewhere in between because as we know, they are the most firmly grounded in reality.

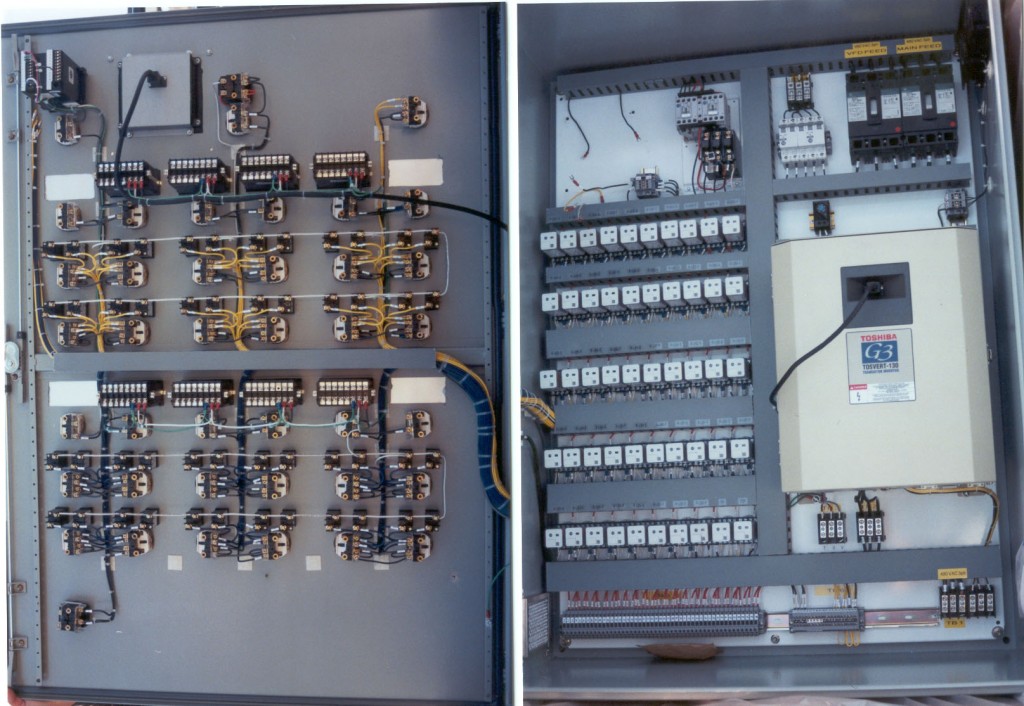

Plant specifications usually dictate what kind of layout an electrical enclosure will have. It is common to use divided wireway to separate AC and DC wiring, finger safe terminal blocks, distribution blocks for high voltage distribution and appropriately sized and colored wiring. For some reason the controller is usually somewhere on the left side of the backplane though either on top or at the bottom while most of the higher voltage distribution ends up on the right. This may be because flange mounted disconnect cutouts are usually on the right and single door enclosure hinges are usually on the left.

I have seen plant specifications where AC and DC wiring must be kept in separate wiring ducts, no dividers allowed. These same specs dictated redundant controllers, redundant power supplies and generally made for a much larger enclosure than usual. I have also seen panels with no wireway at all, wiring was simply tie-wrapped together. I’m sure this made the mechanical designers happy, but didn’t go over well with anyone else.

Regardless of your personal preferences and discipline, it is in everyone’s best interest to have a clean looking enclosure, properly labeled and with enough room for the inevitable work that will take place during troubleshooting and machine modifications. If your plant or company doesn’t have a wiring specification I would be happy to provide a good generic one free of charge. It doesn’t mention the cup-holder you may want, but you can add that yourself!

In my early career, as I worked my way through school, I was an electrical designer for an OEM. One of my projects was a control cabinet for a plastic extruder. Since this design would be used as a standard, I paid careful attention to the placement of components on the inside panel. This was not well-received by the panel builders and the components were too close together for the plant maintenance folks who would eventually deal with it. After that, I involved the panel builders in the placement of components. It’s amazing how much better “my” designs were when they were “our” designs.

After getting my degree and still working for the same OEM, I participated in a committee of plastics machinery manufacturers to add our requirements to NFPA-79. That standard has evolved substantially over the intervening years, but remains a good guide to safe design. It should be on every designer’s book shelf.

–Carl Henning

http://www.PROFIblog.com

I’ve been involved mostly with OEM machine building with no separate cabinet required. We first do a model in Solidworks to make sure all the electrical components fit, then let our techs figure out the best layout when they wire the first machine, and finally update the model to match.

I discuss my ideas with our techs before choosing components and use their feedback. I also like playing around with physical samples (e.g. of connectors) before specifying them.

For building standard machines (or semi-custom machines with a common core), I recommend looking at making custom PCBs (or at someone else making them; I’ve got a salesman trying to sell me on Wago custom break out boards). They’re not right for all cases (e.g. high power, high voltage, or where a design changes frequently), but custom PCBs have worked very well for me.

Some companies’ control cabinet standards are a little excessive. We once bought a nice gray control cabinet to go in an automotive plant — and had to have it spray painted because it wasn’t the exact right shade of gray. That car company had to get bailed out…